Paints, Stains, and More: Choosing the Right Wood Finish for Any Project

Photo: istockphoto.com

The reasons for applying finishes to wood surfaces are several. One is to seal the wood, in order to prevent moisture from entering the grain and to protect it from heat, scratches, or even insect. Another goal is to enhance its appearance, adding color, contrast, shading, or even to change its texture. Among your options in finishing wood are stains, varnishes, paints, and rubbed oil finishes.

Stains

As the name suggests, stains are coloring agents that are used to change the color or shade of the wood. In fact, stains are not technically a finish because a simple stain requires a coat (or coats) of varnish or another finish on top to protect the wood.

Stains can highlight the grain, lighten or darken the natural tones, or change them altogether. In general, stains are applied first, and are often followed by sealers or varnishes. Some combination products are sold in which a stain and a sealer are applied to the wood at one time.

There are various kinds of stains that are distinguished by the vehicle or solvent in which the color is suspended. The stain goes on as a liquid, the solvent evaporates, and the stain dries.

Photo: istockphoto.com

Shellac

This is the old standard, though it’s used less and less often these days, as advances lead to new, quicker, and easier-to-use finishes. It gets its name from the source of the resin that is its principal ingredient, the lac bug, an insect found in India and other countries in southern Asia.

The principal disadvantage of a shellac finish is that water stains it; another is that alcohol dissolves it. One carelessly abandoned glass and its accompanying film of condensation will produce a water stain that won’t go away until the piece is refinished.

Even so, the great popularity of shellac in the past (and among some craftsmen even today) is understandable. In either its white or in its orange form, it’s quick and easy to apply with a brush in a series of light coats. Each should be thin in order to avoid drips or runs. I recommend a light sanding between coats and a final coat of paste wax after the shellac has dried thoroughly.

Photo: istockphoto.com

French Polish

A French polish shines with a mellow, reflective quality that is its greatest appeal—but, since its key ingredient is shellac, it does not protect the wood from heat or moisture damage (again, water-glass rings and the like are a continuing concern). For many pieces of furniture that originally had that finish (or modern copies of such furniture), it really is the appropriate choice. It’ll give your arm muscles a workout, too.

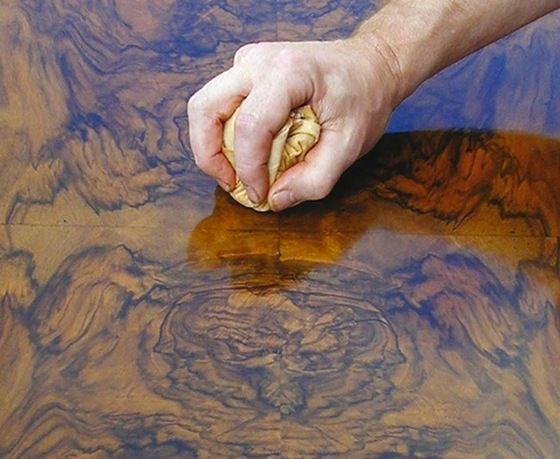

French polishes are not all the same, though the basic ingredients are usually a mix of shellac and alcohol (sometimes with boiled linseed oil or a few drops of mineral oil in later coats). The mixture is applied to raw wood with a rag. Wear gloves when applying a French polish.

Coat the surface using light strokes, working with the grain. Some users recommend a swirling motion, as if you were making a series of Os in script, but still progressing in the direction of the grain. After the first coat has dried, sand the surface with extra fine sandpaper or steel wool. Many coats are required: with each one, the shine will increase. The more you rub, the more the finish will shine.

Photo: amazon.com

Penetrating Oils

These are sold in clear and stain colors, and are easy to apply. They are wiped on and tend to dry quickly and evenly. Penetrating oils are extremely durable and resist both scratching and water damage, because the finish penetrates beneath the surface, sealing and protecting the wood. One result, however, is that the surface itself is left with little sheen or gloss.

These finishes are manufactured in a variety of formulations, some of which have a resin base, some an oil base. Boiled linseed oil and tung oil are common penetrating-oil finishes.

Penetrating oils can be applied with a cloth or brush. Coat the surface thoroughly, after about fifteen minutes (less if the surface is plywood), wipe off the excess. Apply a second coat. There’s no need to sand between coats when using penetrating oils. If you wish to stain the wood, do that before applying the oil finish. Alcohol- and water- based stains work well with penetrating-oil finishes.

Photo: shutterstock.com

Varnishes

The word varnish has become something of a catchall term applied to a variety of liquid preparations that, when applied to a surface, dry to a clear, hard, and often shiny surface. They are good general-purpose clear finishes.

Varnishes are more difficult to use than, say, shellac or penetrating oils. They dry slowly (which means that dust and debris can accumulate on their tacky surfaces as they dry) and the surface tends to bubble. When applying varnish, the room should be warm and as dust-free as possible. Stir the varnish before using it, but don’t shake the container, as that will cause bubbles to form.The brushes, too, must be clean. Overlap your brushstrokes, and apply the varnish in a very thin layer. Don’t over-brush. After varnishing an entire surface, go over it once carefully with the tip of the brush. Don’t apply more varnish, but smooth the varnish already there in long, even strokes.

When the varnish has dried completely, smooth it using extra fine sandpaper or steel wool. Apply a second coat. After that has dried, you may wish to rub the finish with steel wool or pumice. Apply a paste wax, and buff the finish thoroughly.

Photo: istockphoto.com

Paints

Varnish, oil, shellac, and French finishes are, for the most part, clear finishes. Paint, in contrast, is opaque, and usually contains colored pigments.

The pigments are finely ground solids that are suspended in the base material, which may be latex, oil, or other substances (lead-based paint now is no longer available because of the toxicity of the lead). Paints are sold for use indoors and outdoors (exterior paints are much more durable, resisting fading, chipping, and peeling). Most are sold in a variety of lusters, depending upon whether they dry to a glossy sheen; a semigloss or satin finish; or a flat or eggshell surface. Gloss and semigloss have the virtue that they can be washed and even scrubbed; flat or satin finishes have a soft, understated presence.

Before being painted, raw woods need to be sealed with a primer coat. This seals the wood and prepares a surface to which the paint to follow can bond. The primer used should be matched to the paint to be used; read the instructions on the can or consult your local paint supplier.