As fairy doors randomly appear, a neighborhood is enchanted

Before the pandemic, Kate Young didn’t think of fairy doors as a way to commune with her neighbors.

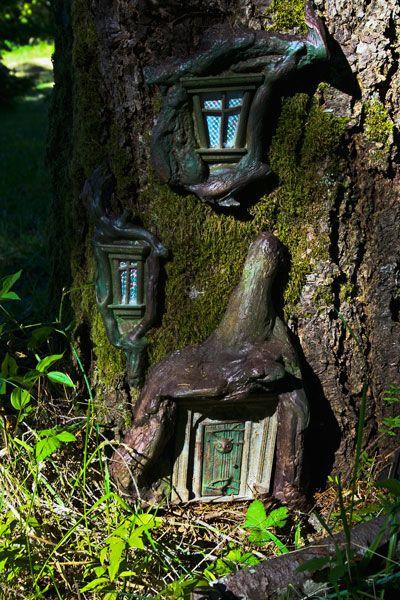

The tiny sculptures she made were something she did for herself, tucking them into the crooks of branches and the bases of trees near her house in Alexandria, Va. A graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design, she started making them four years ago when she was out of work and saw, in a nearby apartment complex, a little door in a tree with a stone path and a bridge. It looked like a fairyland.

She felt moved to contribute, and started leaving miniature gifts such as grocery bags for its invisible inhabitants. But when she considered making them a little clay pumpkin for Halloween, her father objected.

“He said, ‘You can’t take over someone else’s project,’ ” she recalled. So she started erecting her own fairy doors, windows and tiny structures in trees and walls around the neighborhood, unsure whether they would be appreciated or considered an eyesore.

Advertisement“It’s pretty much graffiti, so when I put them out, I’m pretty much ready for them to get destroyed,” said Young, 29, who grew up in the neighborhood of narrow lanes and century-old bungalows.

Mostly, she didn’t hear anything good or bad. Then the pandemic hit.

Unable to go to work or school, people took to walking around. Email chains began. “Who’s doing this?” people wrote of the doors. Their children, they said, were enchanted.

Soon the fairy post office, a free-standing structure she had installed against a dogwood tree at Mount Jefferson Park with a slot for letters to Santa, began to fill up.

“Kids started leaving the fairies letters,” Young said. Envelopes arrived with stickers and hand-drawn pictures, bearing children’s jagged scrawls or the neat script of parents taking dictation. Some were from nearby neighbors, some from Maryland, D.C., and other parts of Virginia.

Who are you? the young writers asked. What are you? What do you do in the night? What do fairies like to eat? Do fairies like bubbles? Are fairies afraid of dogs? Can fairies get COVID?

“I was like, ‘No, fairies are immune to COVID,’ ” said Young, who tries to reply to all the letters. “But the need for them to know their fairy neighbors were OK — it really hit home.”

Young figures she has installed more than 100 doors around the neighborhood. After early polymer clay versions began to break down when exposed to the elements, she now makes them out of resin and epoxy clay.

Many are more than doors — elaborate rooms with furniture and lamps and twinkling lights and front porches. And while Young now has a job at a local native plant nursery, she also runs a business making custom fairy doors and create-your-own fairy door kits.

Her workshop, in the basement of the brick row house she shares with her partner and a housemate, is stacked with boxes and drawers containing materials and glittery objects she has made. Fairy lamps, fairy bottles and fairy long-stemmed roses, each small enough to perch on the tip of a finger. An overturned teacup refashioned into a house, with a door and windows and layers of buttons for roof shingles.

“The backstory is I am a fairy Realtor, so I just build the houses, and the fairies move in,” explained Young, who with her cherry-red eyeglasses and turquoise lipstick and purple patchwork sweater has a fairyesque aura. “I work for the fairies.”

Fairy doors are not just a Virginia thing, and Young is not the only fairy real estate agent. They have appeared in neighborhoods, parks and forests across the United States and in England and Ireland, and materials to make them are available in craft stores.

In Alexandria, the backyard of sisters Camila and Alexa Ballesteros, 5 and 7 respectively, became a hub of fairy activity after their family built a pond with a fountain in the summer of 2020. Since then, 20 fairy houses have sprung up, with one tiny door serving as their portal (the sisters’ parents serve as fairy real estate agents). Now, other children come over to see the growing community.

“We planted flowers and we wrote notes to the fairies,” Alexa said. “We wrote, ‘Don’t worry, we are friends. We salute you.’ ”

In Del Ray, Young walked out on a recent morning to replace a fairy house she had repaired in the nook of a tree on a quiet residential street. She glued down a geode next to its front door, explaining that “everything’s better when it sparkles a little bit.” As she walked, she scanned the streets for potential new real estate (she usually keeps a couple of doors in her backpack for impromptu installations).

Often, it’s kids who notice them first, being closer to the ground and more attuned to fairies.

“They are so small, you know, some of them you absolutely cannot see,” said Jennifer Liao, who lives in Fairfax County, Va., and brought her children, 5 and 8, after she saw a mention of the Del Ray fairies on social media.

“We were looking for things to do outside during the pandemic,” she said. The family followed a Google map where Young marks the presence of the doors. “They loved it so much,” Liao said of her kids. “Who doesn’t love a scavenger hunt?”

Many of the addresses on the map include fractions of numbers, a nod not only to the fairies’ size but also to the proliferation of demi-addresses in a neighborhood of carriage houses, in-law units and additions.

Sarah Lartey’s daughter Grace, 4, is obsessed with fairies, so when Lartey saw the doors mentioned on an email list of things to do with kids during the pandemic, she contacted Young. The family lives in the District of Columbia, but for Grace’s birthday in March, they took Grace and a few friends to Del Ray for a fairy door tour with Young.

“My daughter thought she was the most magical person,” Lartey said. “She came that day dressed as a modern witch and basically explained that she makes the fairy doors as an invitation to the fairies,” she said. At the end, each girl got her own fairy door and a crystal to put in their gardens.

People strolling around Del Ray seem accustomed to the fairy doors. On a recent afternoon passersby helpfully described where to find installations around the neighborhood — from a 2-inch-high portal Young installed at the base of a stone wall to a vivid teal door that Young painted, around 3 feet high, on a tree in front of the Dairy Godmother.

More and more, doors appear that are not from Young. “It’s getting to the point where I’m finding fairy doors that I didn’t know about. It’s the most amazing thing, to also be a fairy hunter,” she said. She encourages people who put out fairy doors to send her photos to add to the map.

One thing she is not is a fairy maker. The doors and houses she puts out are free for any fairies to use, but they must move in on their own.

“I’ve shied away from putting fairies out, because I’m very hyper-aware of how the ethnicity of my neighborhood has changed,” she said, adding that it can be hard to find fairies of color in shops. “I want the kids to picture themselves in it. ... Everybody needs to be able to see themselves in art, especially public art.”

Now that more people know who Young is, she gets presents as well. Broken crockery, gravel and pipe cleaners appear anonymously on her front doorstep, to be used for projects — a sign that at least some neighbors know who she is and support what she is doing.

“I really don’t know most of the people, and that’s kind of awesome in its own way,” she said. “I’ve had preschoolers up to boys in middle school believing in fairies.”

Bahrampour writes for The Washington Post.