Creating Culture that Doesn’t Suck – Good Comes First

Transcript

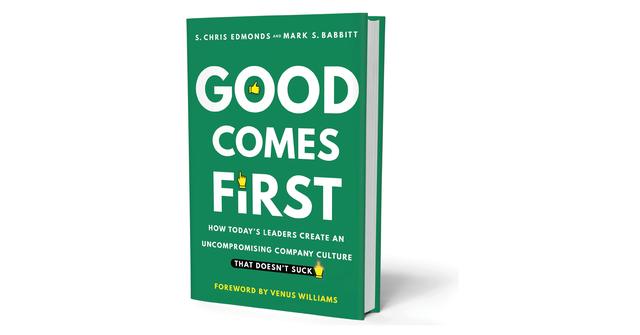

Shane Hastie: Good day folks. This is Shane Hastie for the InfoQ Engineering Culture podcast. I'm sitting down today with Chris Edmonds and Mark Babbitt. Chris and Mark are the authors of a new book, "Good Comes First, How today's leaders create an uncompromising company culture that doesn't suck".

Shane Hastie: Chris, Mark, welcome. Thanks for taking the time to talk to us today.

Introductions [01:01]

Chris Edmonds: Well, thanks for the invitation, and we're excited to be here to talk about how leaders can maybe improve quality of the worker experience with their teams.

Shane Hastie: Great. So before we get in, a little bit about who is Chris, who's Mark?

Chris Edmonds: I am a musician - there's guitars. You're not going to see the video, but I'm a musician and there's no money in that. And that took me a while to discover that. I got a real job. So I've been in the leadership consulting space, particularly around culture for 20 plus years, 25 years. And so I've been writing, I've been speaking, I've been coaching and Mark and I have known each other for probably 10 years on social media and got a chance to meet face to face at a culture conference in Chicago, back, we think, six years ago or so, and had dinner one night and decided, oh my, we have very similar views and very similar frustrations with the quality of leadership, so it took us three years to write this book and the pandemic brought some curve balls, but we're very excited that the reaction to it, the response to it, people, leaders particularly seem to be looking at this whole great resignation with some concern. And that's not a bad thing. I think that's a good thing.

Shane Hastie: And Mark.

Mark Babbitt: I am a Silicon Valley veteran in two different stages, one as an engineer, right after I left the United States Air Force, I did what every military trained engineer does. I went to Silicon Valley and found my first real job and did the engineering thing for about 10 years and decided that the corporate world wasn't necessarily parallel to my views and my goals. And no matter how hard I tried, I could not get my small team to break free from the corporate Boston culture that seemed to be strangling all of us. And ever since then, I've been completely intrigued with leadership's impact on company culture and what's real and what isn't and specifically how easy it is for leaders to believe the About Us page instead of knowing what their culture is really like.

And so once Chris and I got together and we had some same thought processes around why do leaders keep delegating culture to HR? Why don't members of the C-suite let leaders develop their own subculture within, maybe you do have your this is how we get our work done. This is our rules. These are our values, but subcultures, we call them contagious pockets of excellence, they're the ones that are getting the work done. And as long as they're doing the work, well, why do we have all these weird rules?

I've been intrigued Shane, since I don't know, late 1990s. That's how old I am, on exactly how we can make work cultures better.

Shane Hastie: Possibly a starting point. What do we mean when we say culture in an organization?

Defining Culture [03:54]

Chris Edmonds: There's been a number of formal technical definitions. And the reality is that at most leaders look at culture as very much a I'll get to it if there's a pressing need, meaning if it's all in flames, okay, that could be a pressing need, but my focus is getting crap done. It's getting code written, it's getting widgets out the door, whatever it is.

So culture is the way people treat each other and it's the way they cooperate or not to get work done.

Mark Babbitt: I have a very succinct answer. Culture is accidental. It's the way we've worked since the industrial age began, there has been almost no intentional thought given to culture. And until very recently, and even the companies that are famous for their company cultures: free snacks and dry cleaning and shoe shining, and well, if you talk to a lot of people at Facebook, they would say the culture sucks. And Amazon, the culture sucks, and Google the culture sucks.

Free snacks, greatest pay in the world, fun company on the surface, but working here is ultra-competitive, there's no work-life balance, our leaders are ladder climbing jerks, and this should be my dream job and it's a nightmare.

And in those cases, there's no doubt the culture took on the personality of the founders, the CEO, and sometimes that's okay and sometimes it's not.

Culture is largely accidental and that causes harm [05:22]

Mark Babbitt: And that's why cultures are accidental. As a startup founder myself, I didn't give a second thought to what I wanted the work environment to feel like it was all about as Chris said, getting product out the door, impressing the investors. We didn't stop to think about it. And as a result, a startup in Silicon Valley that I was brought in to help fix, they put 110 sales people on a floor in downtown San Jose with no windows, none. And they couldn't figure out why nobody was happy.

They couldn't figure out why sales calls couldn't be met. Completely accidental.

Shane Hastie: Given that culture is accidental and it sort of just happens. How do we deliberately design it or can we deliberately design it?

Leadership attitudes and behaviours need to change [06:05]

Chris Edmonds: Great, great lead. And yes, absolutely it can be deliberately designed. And the first thing we do in "Good Comes First" is help leaders realize that what we're going to ask them do is something they haven't done before. Most of have not been asked to change the quality of their culture, to change the employee experience from maybe not so positive to positive. All of that is rather alien. And so literally we tell them we can help. We're going to take some skills you have and we're going to apply them. And so our focus in "Good Comes First" is that employees need to feel respected and validated for their ideas, efforts and contributions every day.

So as you can tell with that as almost a foundational belief, there's a lot of stuff that leaders should be doing in order for that to happen. They have to be engaging, they have to have conversations with people on an informal basis, they need to pay attention to understand the quality of the work relationships and how easy or difficult it is to get stuff done.

So we tell leaders just as you have experience with setting performance targets and coaching to those being delivered sometimes maybe even having to hold people accountable for the delivery of performance stuff, good, let's apply that to respect and civility.

So let's define expectations, meaning we help leaders define desirable, respectful interactions in behavioral terms.

I do what I say I will do, all of a sudden that creates a whole different dynamic about how I show up, what notes I make in a meeting, how I follow up because it's my task or it's my team. So there's some really what we hope are easy avenues to be able to have leaders think, okay, I just need to do a better job of holding people accountable for performance. But I also need to define what we mean by respect. And then I have to model it. I have to coach it. I may have to mentor someone who's not doing it. And obviously what you could hear Shane is we're asking for a different way of leading the business when we're asking leaders to invest an equal amount of time in managing respect.

Shane Hastie: Thanks. Regular listeners to this podcast will know that this aligns beautifully with a lot of the things that we do talk about here.

For the recently appointed team lead, or somebody moving from a technical contributor to a leadership role. Very often they haven't been trained in this stuff, they're the best technologist and they care deeply about the people they're working with, might not be terribly good at expressing that. Where do they learn? How do they learn this?

Leadership requires different capabilities and training from engineering [08:54]

Mark Babbitt: Most do not. And Shane, as a young engineer in Silicon Valley, I was that guy. I don't know if I was the best technologist, but I got my work done and I enlisted the help of others well, so I created this concept of teamwork so we could all get our work done. And pretty soon I was a manager at 26 years old, and I had no clue what I was doing.

And my mentors, my bosses were very much industrial age practitioners. He's like, just get the F-ing work done. I don't know what the problem is here. I don't care if she's happy, get the work done. I don't care if he's upset about something I said, he's got a job to do. He's being paid to do the work.

And I approached leadership differently. Even way back then I asked questions. I said, what's working well among our team. What's not working well, what can we do better? And my bosses went, what you're asking are stupid questions. Even back then, I was trying to build a subculture where I, as a leader, could learn from the people I was supposed to be leading. And it was so unusual back then that I was written up for it. It was a negative. And that's when I decided this isn't probably for me. So getting back to your question, we don't train them.

Don’t allow toxic behaviours in [10:05]

Mark Babbitt: And by the way, it's not just engineering, it's not just technology. We take the top performing sales people, they may be total jerks, they may be sexist pigs, they may be racist fools, but because they meet their quota, 132% quota every quarter, we're going to make them the new manager, right? Which brings us in full circle back to the respecting that Chris mentioned, because we can no longer promote those people because their values are causing disruption in every other element of the company.

So they may be personally doing well, but the person who was just bullied does not, and they don't feel psychologically safe. And because they don't, now they're not doing their work very well. And now we have this division of sorts and now things become political and drama sets in.

Well, we can't hire those people anymore let alone promote them, or we don't have a respectful workplace. And so again, full circle back to your question. Young leaders, new leaders are in a really tough spot, and we have to start thinking about what we want our subculture to be even if we're not completely aligned with the overall culture.

Respect is a cornerstone of effective leadership [11:07]

Chris Edmonds: Shane, if I can, let me add one of the key things that Mark is referring to is that the role models that these new leaders have had may not at all be set about respect, be concerned about civility in the workplace. And so to some extent, just as Mark described, you got to go against the current and that's not going to be easy, but in your own little team, it can be a bit isolated and maybe even insulated. And it means you can do a lot of this rather formal. We're going to respect each other here. We're not going to cuss. If we cuss, we put a dollar in the jar.

I remember some teams I worked on where a guy came in the morning, slammed a 20 in the jar said that will not hold me to lunch. So that's not necessarily reducing undesirable behaviour, but the idea of, if you expect a team to cooperate well, to share information well, to work together, to solve tough problems, then you have to build a respectful environment where people literally know, well, if I've got this task coming up and we've got this deadline, I need her because she's brilliant and she'll share with us.

We'll all learn as she kind of drives us through that particular task.

That takes a lot from a leader who might be in an environment where they believe I have to know everything. I have to be real about everything. I have to teach people stuff I've never done before. And so the reality is no, you're just human and it's fine, nothing more than that, but it means that you've got to build a team where cooperation is the norm, and that's not going to happen without respect first.

Annual performance reviews are a toxic relic of old-style management thinking and have no place in the modern workplace [12:50]

Shane Hastie: What about some of the extrinsic stuff? One of the dysfunctions that I've certainly seen in many, many organizations is we ask people to be great collaborators, work together in this team, cross-functional, self-organized and they're doing that. And then once a year, we stack rank them against each other and decide who gets a bonus based on-

Chris Edmonds: Stupid.

Mark Babbitt: Oh, Shane, you do not want to get us started on annual performance reviews. This podcast is only supposed to be 40 minutes or so, and that could take a couple hours, but your point is well taken. And it's a huge red flag, especially the young engineers, the young people that are going into STEM work. If you are going to work for a company that is still doing annual performance reviews run away.

Why would you go to work for a company where you only get told how well you're doing once a year, that's an old school company and your gen Y, gen Z mind is going to explode over the next 12 months if you don't get feedback more often. And performance reviews are a sign of days that are gone by long ago, and Chris and I are doing our best to make them the dinosaurs that they are.

Shane Hastie: So what do we replace that performance review with? Well, people need feedback. How do we give them good feedback that is going to be actionable? And what do we do with this bonus incentive in particular?

Providing feedback frequently and safely [14:15]

Chris Edmonds: It's interesting because I remember having this very conversation probably 30 years ago as an internal consultant in a quasi-governmental financial unit. I may have given away too much already, but it was old school. And sometimes in the financial industry, those old habits are very, very, very hard to break. But they are in many organizations anyway, and it's as if you think about, and I'm going to pick on Mark here a little bit, Mark's been a baseball coach for 35 years. And if you think about a baseball coach that would sit in the dugout and yell at everyone for making mistakes and never praise any effort or hitting or pitching or backing up, that's going to be a team that doesn't believe in themselves. And it's going to be a team that doesn't want to work for that coach.

So the idea of how do you create an environment where every day people are hearing how they're doing? There's a means by which they are reporting their sales, right?

Reporting their output, but also asking for help. That takes a degree of trust and respect, that is not common in our organizations. And every bit of it is driven by the leader. They have to be willing to say, okay, within this environment, we have an annual performance review that force fits us into this weird hierarchy and the top 10% get money and the rest of us don't get a thing. We can't fix that. So let's at least create an environment where we're honestly looking at our performance, both as a team and individually and praising the progress and trying to help with our isn't and being in essence, grateful for the folks that really do treat us well, treat us respectfully, help us, and I'm going back to that pocket of excellence thing. It's like, if you can insulate yourself from stupid policies, it will help you for a while.

Mark, what do you think?

Mark Babbitt: Two things to answer your question directly. One, instantaneous feedback. Drama happens when people feel insecure, period. And there's been a million studies done on this. There's been more recently studies that show if we don't do that, if we have enough respect for people to take on a problem right away, and people actually feel respected by their boss, by their colleagues, by the people in the C-suite it's 18 times better an indicator than almost any other factor in work. Matter of fact, it's so important. It's a today's workplace that it's more important than pay perks, benefits and training combined. That's how people rated this feeling of being re respected.

Well, there's no better way to show respect than to give instantaneous feedback. So don't wait until December 7th, every year, sit down and have a real conversation.

Again, what's working well, what's not, what resources can I send your way to help you do even better? Those are the kind of questions we have to ask, not every Friday at 11:00 o'clock you and me sitting in a dark room, but just walking down the hallways. And so that's number one.

Random acts of leadership [17:19]

Mark Babbitt: Number two, it gets right back to what we just said. These random acts of leadership, and we use this example all the time, but we had a client. He was famous for walking down the halls, but he always had his head in his phone. He was never looked up. You never made eye contact. He never built relationships. So we encouraged him, his name was also Mark, to walk to the halls and actually ask questions.

I saw you were working late last night, what are you working on? Why aren't you home with your family? What resources do you need so you can go home in a decent hour?

And when he started doing that, it was instantaneous culture shift. Literally people went to work the next day going, you're not going to believe what Mark did. He actually stopped me in the hallway last night and asked me what I needed. He asked me what I needed. Right now, this is a very old school company. And this was the IT team 600 people within a 6,000 person company and instantaneously, he built his own subculture just by asking those questions and then acting on it.

Asking for feedback and giving feedback right away. Boom. The culture changed literally overnight.

Shane Hastie: How do we make that feedback. I want to say safe and respectful.

Creating a safe environment for feedback [18:28]

Mark Babbitt: Well, and that's where values come in, Shane. And Chris, I know this is the direction you would go to is let's just say that work did not get done on time. Well, anybody can scream and yell. We're all very good at that when we get right down to it and not just at work right, when we lose our patience with our kids or our spouses, our friends, our extended family. We're pretty good at just sounding off.

Humans have been practicing that forever. We're pretty good at it now. Right? But what would happen if you actually sat down and said, I'm frustrated the work didn't get done, but I'm not here to punish you. I'm here to find out why. So next time this isn't a barrier to success, right?

And if you start a conversation respectfully like that, and you envelope that around your values and we encourage all of our companies, not just those stupid values that get slammed up on a poster in the lobby and in the conference rooms, but real values that we're all accountable for living, well now we're having an emotionally intelligent workplace, intelligent conversation that makes this situation better.

As Chris and I run through our clients, and now readers of "Good Comes First", it's one of the first questions they ask, well, how do I go from this reactive volatile, at times intimidating, especially the alpha male leader types, they're starting to figure out maybe I'm self-aware enough to know that this intimidation thing I've been working off of for 20 years is not exactly psychologically safe, right? It's not the best way to handle this conversation. Well, how does somebody change overnight? And the answer comes full circle right back to let's show people respect.

Chris Edmonds: And if I can tie into that, one of the pieces that's critical in our organizations today is there are typically clear metrics for performance, for output. And I would remember, oh God, I'm going to date myself. I went to America Online in Tyson's Corner, Virginia, and they had, oh my God, T1 lines going in. And it was the entire brain of AOL back then, this was '95, '96, but they had metrics for client acquisition, for obviously how much those clients were paying. How many of those little, oh my God, three and a half inch discs were being sent out with the AOL application to load, et cetera.

Metrics for culture and respect [20:43]

Chris Edmonds: Well, their mindset was, we need data. And so it's a very, very common expectation, especially again, we go back to the industrial age, we're here to deliver code. I want to know how many lines I want to know how many mistakes we had et cetera. And what is fair is then let's look at your performance standards and see how well you did on them. Now, does that happen monthly? Does it happen annually? Hopefully it's more than annual, but then we want to say, okay, good, managing results is half your job as a leader, the other half is managing respect and let's create some data points that are undeniable, just as performance monitoring delivers. Let's look at respect monitoring and literally we're able to help clients create, again, observable, tangible, measurable behaviors and measuring them, allowing employees to do an anonymous feedback survey at least twice a year, about how well their boss, he or she is modeling these behaviors.

And that's an interesting dynamic. Once an organization says, okay, productivity is a really good thing, but if we have people feeling respected, productivity goes up. So, hmm. Maybe we need to actually honor and almost formalize the expectations of respect.

And we do assessments for clients because it's kind of a weird thing. How do you measure values? Well, we can help you do that, but we get the opportunity to help employees to rate their bosses on a one through six scale on their specific behaviors. It's not something that Mark and I come in and say, you have to do this. It's what makes sense? What are your benchmark players doing? And let's duplicate that.

So what it allows is just as leaders are comfortable with performance data, we have to give them the tools to be able to manage values data.

Shane Hastie: So what would some of those metrics look like for a company?

Mark Babbitt: Great question. And it depends almost exclusively on which values they choose as their north star.

Chris used a great example earlier. The value might be integrity, but we can't just say, and we've done this. We've literally done this. We've had a leadership team. We asked 20 of them. What integrity means to them, we get 19 different answers.

So collectively we have to define what that word, what that value means within these walls. And then once we have that definition, we can just say, oh good, throw it up on that poster. Now we have to say, okay, well what are the three to five behaviors that might indicate whether or not we're living that value? And the example Chris used earlier was I do what I say I will do, or I keep my promises or I'm truthful in my communications.

Well then on that one to six scale, we ask peers, colleagues and people who work for that leader, does Mark keep his promises? On a scale of one to six, how often does that happen? And now we've taken this incredibly human value and we've quantified it. And when somebody gets a five or a six out of the one to six scale, they're doing pretty good at that very human value. But if they're down in a one or a two, it's a wakeup call. It's somebody saying, holy crap, I actually prided myself on that component of my leadership.

By the way, I gave myself a five and a half and my team only gave me a two and a half. Well, I got some work to do. And so it really comes down to making those human values put them in a quantifiable form. We said, this we're speaking. We said for people to be held accountable to values the behaviors that demonstrate those values have to be accountable. And until they're accountable, we can't hold people accountable.

Examples of values metrics applied [24:32]

Chris Edmonds: Let me give you another example. One of my clients has a, it's a very, very small business, but 50 people in the whole company and they wanted a fun value. And I thought what some people think is fun may not be fun to others. And I described a client where some of the feedback we got in one of their early assessments was that the fun in that company meant teasing by senior leaders who could absolutely crucify you with a snide remark or a literal toxic conversation and there were no consequences.

And so they began to say, Hmm, maybe this respect value is more important than a fun value.

And again, it goes back to the idea of if you're able to say respect is I do what I say I will do. I will keep my promises. I recognize others' contributions on a day daily basis. And I'm a direct report to that boss, and I know that I'm actually going to give feedback and my score is not going to be attributed to me. It gives us the confidentiality piece, but we still use, as an example, one client has six values. They've got about 15 behaviors and the president, they did this survey first in November of 2018, and the president scored 4.9 to about 5.5 on all six. And he went, that's beautiful. And I said, it is beautiful, but you're short on two, we'll coach to that. And he says, I'm only two percent, you're short.

And then we looked to see the lowest front-line leader in the field, and this guy averaged threes by his direct reports. And I said, okay, now what you can see is these values that are often aspirational, that doesn't help. Aspiration doesn't help because people get focused upon the only thing that gets rewarded, which is getting crap out the door.

But if you are saying you want to get crap out the door in a way that is civil to customers, to vendors, to peers. Now you've got some data that is undeniable. And I always get folks who say, did they fire that guy? And here we are four years later, no he's still in place. He's getting coaching. He's doing much better. He's not at fives yet. But what it allowed those folks to do is say, okay, we've got leaders that are doing really well on our behaviors and they're performing well. Their teams are performing well. Hmm. I wonder if we can work towards that end.

Shane Hastie: Switching tack a tiny bit. We're now at the beginning of 2022, we've come through the last two years of the pandemic. Things have changed radically. Remote has become the norm. We're starting to see a bit about hybrid back in the office. My assertion is that a lot of us have figured out remote work works. And why would we sign up for three hours a day commuting and so forth?

But this also brings a whole lot of additional challenges. How does this play out in the post-pandemic world?

Bringing these ideas into remote and hybrid workplaces [27:41]

Mark Babbitt: That is the best possible question into day's workplace. And at the very top of the show, Chris mentioned that it took us three years to write this book in part because the pandemic hit right in the middle of that and the manuscript was almost done, and the original manuscript said, leaders have got to start accepting remote and hybrid work as real. It's what people want. It allows them to have that better life balance. It is the wave of the future. And then the pandemic hit and the future was right frigging now, so we had to stop and we had to rewrite that whole section of the book because now we had case studies. We had real world scenarios where people were learning how to work remotely on the fly and globally a across the world. And some people, some countries did it very well and some did not.

And so there were all kinds of good stories and horror stories. And in the end, what people realized is they actually, for the first time ever for many of them had a say in where and win and how the work got done. And I like being here with my four-legged kids. And I like being here for my kid kids. And I like being available to my elderly parents or extended family. I like going to my kids' soccer games and baseball games. And then the pandemic starts to come to a close and the old school bosses say, forget all that. None of that happened. Get your butts back to the office.

And now you can't be there for your animals and your kids and your grandma. And know you can't leave at 3:30 to go watch the soccer game. We're taking that all back.

We don't have a great resignation, we have a quiet revolution [29:24]

Mark Babbitt: And this is why we say we don't have a great resignation. We have a quiet revolution. People have said not only no, but hell no. Shane, you said the best. I know remote works for me now, and if you are going to insist on me losing that, I'd rather go find another job. Thank you very much.

And in the United States alone, what's the number, Chris 48 million people?

Chris Edmonds: 48 million US workers in 2021 voluntarily left their jobs. 48 million.

Mark Babbitt: And that's just not a record saying that shatters by 10 times the previous record keeping. And so people have learned, I'm not going to work in the old way. The old normal is not good enough for you. I will work with you to help create the new normal and the new company culture and new expectations. And yes, we're going to fall on our faces once in a while, but we're all going to work together to create this new or next normal that we're all going to thrive in, not just the company.

Shane Hastie: How do I carry that respect and that rapid feedback and all of that into this remote-first environment?

Chris Edmonds: It's interesting because obviously there was video conferencing becoming much more than normal in the last 10 years and what the pandemic did is mandated, right?

And yes, there were a lot of companies, hospitality particularly that closed. They didn't even have the opportunity for Zoom meetings, right? Their jobs disappeared. And that's a huge negative impact.

And what is sad is that leaders were scrambling for some sense of control, for some sense of, I need to keep my fingers on all of this, and I don't quite know how to do it, especially in a remote way. So I'm going to use the same factors that I was trained often again, bullying, intimidation, demeaning, dismissive, ad nauseam on the Zoom calls. And then I'm supposed to, when the "pandemic cases" begin to lower, and we can ask people if they'd like to come back into the workplace, we'll darn it.

You come back because it's the only way I know how to manage our staff. And as Mark said, huge, huge, huge, huge disconnect. And so can team leaders create a respectful environment in a hybrid setting, in a Zoom only setting, in a scenario Mark and I were on a call at 2:00 in the morning, our time last year with a potential client who was in Dubai. And I'm not necessarily articulate at 11:00 o'clock at night anymore, much less 2:00 in the morning, but it was just what was necessary. And we were all on Zoom.

And so there's a need to understand that the pace to face to face meetings and an environment like a "Good Comes First" company where respect is really expected, it's much, much harder to do that in a remote setting and in a hybrid setting.

And so the leader really has to invest way more time and energy to be able to create an environment that's fair for most. Maybe it won't be fair for everyone, that validates people for their contributions, duh, and that looks for new ways of getting stuff done more efficiently because we're not all in the same building anymore.

Mark, anything to add there?

Mark Babbitt: I'd say we talked earlier saying about random acts of leadership. And I just heard about one just this morning that I thought that is just brilliant.

Examples of random acts of leadership [32:45]

Mark Babbitt: A manager had gotten an email from a key employee and a team leader at 1:39 AM. And the email was eloquently written and answered all the questions everybody had and got the product launch off to a great start. But the leader, the CMO wrote an email to that person and said, look, if this works for you, given your family considerations, I know you have kids and all that, to be sending emails out at 1:39. I'm not going to tell you otherwise, but I need you to know that I do not expect you to be up until 1:30 in the morning writing emails. If you are behind, just tell me.

If you need help or more resources, tell me, but I know you got to get up at 6:30 in the morning to get your kids off to school. So a 1:39 AM email again, if it works for you, that's great. But it sent off a red flag to me and I need you to know it's not required. It's not expected. And that sent shock waves through the 16,000 person employee business saying, holy crap, this guy gets it right.

And again, culture-changing, life-changing, work changing in one email, one empathetic modern day next to normal response to an email went viral.

Shane Hastie: Great story. Gentlemen, first of all, where do people find the book?

Chris Edmonds: The book is available at all your expected brick and mortar outlets. We actually found the book here in Colorado at two different stores that are Barns and Noble here, but it's all on the online bookstores. You can learn more about the book and about us goodcomesfirst.com.

Shane Hastie: And where do people reach out to you if they want to continue the conversation?

Mark Babbitt: And we hope they do. Chris and I, even though we're old white guys, we are both entrenched in social and digital media. So you can find us very easily on Twitter, on Facebook, we answer our own emails. We do not have a social media manager. We believe that digital communication is the start of a mutually beneficial relationship. So we encourage everyone to go to Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and find us.

Shane Hastie: And I will make sure we include those links in the show notes.

Gentlemen, thanks very much. It's been great to talk to you.

Mark Babbitt: Thanks, Shane.

Chris Edmonds: Thanks for the opportunity.