Energy-Efficiency Road Map: Whole-Building Envelope Sealing

Homes and buildings consume 40% of the nation’s energy. On average, 30% of this precious energy is wasted, according to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), and a good portion of that waste is lost through small leaks in heating and cooling ductwork and through the building envelope itself.

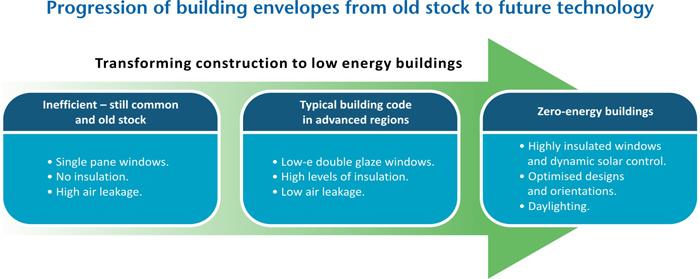

Since the early days of building energy efficiency in the 1980s, airtightness has been one of the most affordable and most effective ways to improve building performance. Over the past few decades, builders have gotten used to airtightness testing and have learned how to meticulously caulk and seal every crack and crevice. Today, modern building codes include airtightness standards, measured in air changes per hour (ACH) as measured by a blower door test.

We’ve come a long way since those early days of efficiency. New homes today use about half as much energy per square foot for heating and cooling, in large part because of this shift to airtight construction.

Yet 20 years into the 21st century, we are still doing all of this sealing by hand. Wouldn’t it be great if you could hook up your blower door and those cracks were sealed for you, without using cases of caulk and foam?

Enter Aerosols: A Whole-Building Envelope Sealing Solution

Aerosol whole-building envelope sealing, originally developed with DOE funding, does just that. This high-tech process uses a dry fog of aerosol sealant and pressurization from the blower door test setup to find and seal leaks. Escaping air carries the cloud of tiny sealant particles to leaks where the specially formulated “sticky” particles accumulate until the leaks are completely sealed.

Computer software connected to the blower door test equipment monitors the entire process, verifying that the airtightness goal has been met. Aerosol envelope sealing, Werling says, makes it possible for new homes and existing buildings to achieve the stringent levels of air sealing demanded by many of today’s building codes and advanced certification programs such as the DOE’s Zero Energy Ready Homes.

Simply, I love this technology. It uses the laws of physics to precisely seal the building,” he says. “The aerosol particles are like tiny leak-seeking missiles, searching out and destroying energy waste. That’s my kind of weapon!

Advancing Technology for Greater Energy Efficiency

The seeds of this solution were sown three decades ago at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). A researcher named Mark Modera joined LBNL in 1978 and helped build some of the very first blower-door technologies. Later, he led projects examining air leakage from HVAC ducts and showed that manual duct sealing could reduce leakage significantly.

But that process was laborious and time-consuming. Convinced there was a better way, Modera became obsessed with devising a method to automatically seal ducts from the inside out.

With DOE funding, Modera and his team began testing a method of duct sealing that relied on an aerosol sealant. The method worked by pressurizing the duct system and spraying the sealant inside. In this pressurized environment, the only place for sealant to escape was through cracks and holes in the ductwork. Sealant particles would deposit on the edges of these cracks and penetrations until they were completely sealed off. The process was fast and effective, drastically reducing air leakage.

Hurry Up and Wait: New Duct Sealing Technology Seeks a Market

In 1997, after years of testing and refinement, Modera and LBNL created a new company called Aeroseal with the intent of commercializing the product. Unfortunately, the world wasn’t quite ready.

“There was no market for duct sealing technology,” Modera says. “But this was my baby, and I’d spent all of this time jumping through a million hurdles to do it. It would have died on the vine if I hadn’t pursued it.”

In 2001, having exhausted his savings, Modera sold the technology to Carrier, the multinational air conditioning and home appliance corporation. Although Carrier saw great promise in aerosol duct sealing, its efforts to market the technology fell short. In 2009, the company tasked employee Amit Gupta, a product expert, with determining how best to penetrate the market. “When I started looking into it,” Gupta says, “I saw amazing potential.”He suggested some marketing ideas, but then the global financial crisis at the time disrupted those plans.

Meanwhile, Modera had retained the right to buy back the technology when he sold it to Carrier, and Gupta believed in the technology so much that he was willing to leave Carrier and raise private funding to launch a new company, again called Aeroseal. Modera, who had since joined the faculty at the University of California at Davis (UC Davis), agreed to participate as a consultant. For the next decade, with Gupta at the helm as CEO, Aeroseal enjoyed steady growth.

Aerosol Sealing: Making It Marketable

Modera’s position at UC Davis enabled him to further test the possibilities of aerosol sealing, including whether it could be used to seal entire building envelopes. He began working with Curtis Harrington, R&D engineering supervisor at the UC Davis Western Cooling Efficiency Center, which was part of the DOE’s Building America Alliance for Residential Building Innovation research team.

A 2012 Building America project allowed Modera and Harrington to test the process in the lab.

“We built a 4-by-8-foot plywood box and put holes in it; that was our building,” Modera recalls. They performed several tests to see how different variables (such as pressure inside the box and injection rate of the sealant) would affect the envelope sealing process. All tests successfully sealed the enclosure to nearly zero leakage in less than 30 minutes.

After demonstrating that the Aeroseal technology could effectively seal a leaky box, the team began field testing multifamily buildings in Queens, N.Y., , followed by aerosol sealing six single-family homes in Clovis, Calif. The homes ranged from 2,000 to 3,500 square feet and were sealed after the drywall was installed and taped. Each of the six homes was sealed in less than 2 hours to leakage levels ranging from 1.7 to 5 air changes per hour at 50 Pascals (ACH 50).

As these field studies progressed, Dave Bohac, director of research for the Center for Energy and Environment (CEE), procured funding to apply the technology to new and existing multifamily apartment units in Minnesota. Two Building America projects followed.

Field Testing Aerosol Sealing in Single-Family Homes

In 2016, the Building America team, led by CEE, partnered with Aeroseal, UC Davis, University of Minnesota, and Building Knowledge to test the technology in new single-family homes in California and Minnesota. The goals were to:

In this latest round of field testing, the aerosol sealant was applied in homes constructed by two builders in Minnesota and two builders in California. Most of the California homes had crawlspaces and sealed attics; most of the Minnesota homes had basements and ventilated attics.

Again, results were promising. The California home testing showed that the aerosol whole-home envelope sealing method is very effective at sealing air leaks. The homes achieved an average airtightness of 1.09 ACH50, nearly 80% below the California building code requirement of 5 ACH50. This demonstration also showed that aerosol sealing could take the place of several manual sealing steps, potentially saving time and money.

In both California and Minnesota, researchers also experimented with applying the aerosol sealant before drywall was installed. “When we started, most sealing work was done [by builders] after drywall installation,” Bohac says. “We wanted to see if it made sense to apply aerosol sealing earlier in construction.” One advantage of applying the sealant before drywall is that it addresses leaks in the exterior wall.

In Minnesota, after aerosol sealing, about half of the test houses met or exceeded the Passive House standard of 0.6 ACH50, the most stringent air-sealing standard in North America. “Builders here are used to building tight,” Bohac says, noting that since 2015, new homes in Minnesota must achieve 3.0 ACH50 or better. “But getting down to 0.6 ACH50 was impressive.” The tests also showed that aerosol sealing could be performed successfully in cold weather.

As part of a current Building America project, researchers are testing this technology in existing homes. Some specific goals include developing guidance for how to best protect interior surfaces such as flooring, fixtures, windows, outlets, and switches.

“Sealant does not discriminate when it’s trying to seal something,” Harrington says. Surfaces must be protected but still allow enough air to flow through so cracks can be sealed.” Existing homes with crawlspaces have proven especially challenging. Harrington is also exploring whether it’s possible to seal from the attic—a strategy that could open up new possibilities for sealing existing homes and apartments.

“Right now we’re doing all of this work during change of occupancy,” Bohac explains. “The advantage to sealing from the attic is that you could seal completely occupied houses.”

Advantages of Aerosol Whole-Home Sealing: Eliminating Air Leaks—and More

Aerosol whole-home envelope sealing has changed the game when it comes to reducing air leakage. “You can set a target and stop whenever you reach it,” Harrington says. “And you can achieve a much tighter home than [if you were] doing it manually.”

In addition to the dramatic reduction in air leakage, aerosol whole-home sealing offers other advantages:

The technology keeps improving, too. Software has been updated to support the system’s “smart nozzle stations,” which deploy the aerosol, to work independently from one another, relying on temperature and humidity data from wireless sensors to customize how much sealant is delivered to each room. The software tracks the progress in real time so little to no sealant is wasted.

Researchers are also testing other applications of this technology, including the possibility of sealing natural gas pipelines from the inside.

Aerosol Sealing: A Path to Mainstream Adoption

Gupta’s company licensed aerosol whole-home envelope sealing in 2015 under the name AeroBarrier. This time, the experience was completely different from when Modera struggled to launch Aeroseal in the late 1990s.

“The world was way more receptive and interested,” Modera says, adding that although AeroBarrier is newer than Aeroseal, it could grow more quickly as more states and jurisdictions adopt stringent ACH requirements.

According to Gupta, Aeroseal has been used in all 50 U.S. states and in 27 countries. Mandalay Homes was the first U.S. production builder to use AeroBarrier for all of its new projects, starting with 115 homes in 2017 and 2018. In 2021, seven of the 29 projects recognized in the DOE’s prestigious Housing Innovation Awards used AeroBarrier.

The technology has received accolades since its official launch, starting with Best in Show and Most Innovative Building Product at the 2018 International Builders’ Show. In 2020, AeroBarrier won the Best Green Building Product award, and in 2021, AeroBarrier Connect software won Most Innovative Software.

Although it’s nice to be recognized, Gupta says the more urgent goal is deploying the technology where it can make the most impact. “The world needs it,” he says. “The next two decades are going to define where we will be in the fight against climate change. If we can apply our leak-sealing technologies to most of the world’s commercial and residential buildings, we can eliminate 1 gigaton of carbon emissions each year,” the equivalent of removing 25% of the world’s cars from the roads.

In June 2021, AeroBarrier announced $22 million in venture capital funding, thanks to venture capital nonprofit Breakthrough Energy, with participation from Energy Impact Partners and Building Ventures. Bill Gates founded Breakthrough Energy to invest in the technologies needed to avoid climate disaster. AeroBarrier will use the funding to boost research and development as well as marketing, and to increase support of its dealer network.

“This funding ensures our team can reach its goal,” said Gupta in a press release. “We are doubling our focus on innovation to make our technologies even easier and more cost-effective to deploy throughout the world.”

The success and potential impact of aerosol whole-home envelope sealing is exactly the kind of “lab-to-living room” research the Building America Program was created to develop. In my 28 years working toward zero energy homes, this is one of the clearest signs of progress I’ve seen—an innovative, science-based process that precisely improves building performance. It’s a true game-changing technology.

About Building America’s Research-to-Market Plan

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Building America Program has spurred innovation in building efficiency, durability, and affordability for more than 25 years. Elevating a clean-energy economy and skilled workforce, this world-class research program partners with industry to leverage cutting-edge science and deployment opportunities to reduce home energy use and help mitigate climate change.

The Building America Research-to-Market Plan identified three integrated road maps:

Each of these road maps is designed to strategically tackle the integrated challenges related to achieving wide adoption of energy-efficient and healthy, high-performance homes.

Eric Werling is national director of the Building America program for the U.S. Department of Energy. He’s an expert in residential energy efficiency, indoor air quality, and building sciences and is focused on reaching zero carbon emissions in the next decade.