The Heat is Still On: Climate and life at 3 degrees

Heat and health

As I write this article, it’s a little after 9am on day three of a combined heat and humidity event in Brisbane that the Bureau of Meteorology has classified as a severe heatwave. My trusty BOM app tells me that the temperature is 31.8°C, but the ‘feels like’ temperature is already 37.4°C.

Day one of this event felt like a typical warm Brissie day, but it was stifling by evening as the usual cool failed to arrive on schedule. This was just a taste of what was to come. Heeding the forecast, I got up extra early on day two to close up the house and keep out whatever I could of the day’s heat. I shut the windows and doors, shoved sheets against under-door gaps in lieu of door snakes, and carefully put cardboard over windows that didn’t have coverings. I used Blu-Tack for this, but by 10am it had melted and the cardboard had fallen, leaving me to bring out the more reliable gaffer tape.

I live in a 1920s Queenslander. Charming to look at, these houses are basically made of cardboard. They have virtually no thermal mass and have gaps everywhere, so without concerted effort the inside quickly reaches the same temperature as outside—or hotter, if the heat passes through the glass and there’s no breeze. This rapid heat exchange can work well in a warm climate like Brisbane’s as long as the day doesn’t get too hot and—very importantly—the nights are sufficiently cool to reset the temperature, ready to start again the next day.

This particular week’s heat and humidity event was unpleasant, or ‘oppressive’ as my BOM app kindly forewarned me as I needlessly rechecked the forecast before bed. It is also potentially dangerous. Heat kills people. More heat kills more people. And when it’s humid our bodies’ natural evaporative-cooling mechanism, achieved through sweating, doesn’t work. You still sweat, but the water just sits on your skin, refusing to evaporate, as you accumulate heat. When it’s hot, your heart has to work harder to pump thicker blood around while trying to get it closer to the surface of your skin in a futile effort to cool your body down. Your other organs are also under pressure.

You’re at greatest risk of becoming ill or dying in a heatwave if you’re older or less mobile or have a disability or an underlying chronic condition. You’re also at high risk if you can’t access or afford the means to keep sufficiently cool, such as air-conditioning at home or in public places. You’re at risk if you’re undertaking any kind of physical labour or otherwise being active in the heat; if you’re homeless or living in institutional care, such as an aged-care facility or a prison, or if you live in poor-quality housing; if you live in an area where there are few trees or where you don’t feel safe opening the windows at night.

Ambulance attendance, hospitalisations and deaths increase with the duration of a heat event and are associated particularly with higher night-time minimum temperatures. Much like our homes, if our bodies can’t shed their accumulated heat each night and reset, we begin the next day from a higher baseline.

Our hottest decade

All the weather we experience today is happening in a world that has, on average, already warmed 1.1°C since industrialisation. That’s only the average, tempered by the Earth’s oceans. Australia, as a large land mass, is heating up more rapidly than the average, with warming now at 1.5°C. Because of the wet La Niña event last year, 2021 was the coolest for a decade—a decade that had been the hottest on record. The hottest ever decade just past will be remembered as one of the coolest in the lifetimes of my kids, now teens.

Throughout Australia, the number of annual ‘hot’ days is increasing. Heatwaves are becoming longer, more frequent and more intense. Night-time minimum temperatures, the ones we rely on to reset our bodies and homes overnight, are warming faster than daytime temperatures—our nights are getting relatively hotter, and increasingly oppressive.

There’s about a twenty-year lag between greenhouse-gas emissions and the associated observed warming, meaning that our weather today is the result of all the cumulative emissions leading up to around the time Kath & Kim premiered on the ABC and Queens of the Stone Age topped Triple J’s Hottest 100. In 2002 in Australia, state and territory leadership was dominated by the Labor Party: Bob Carr, Steve Bracks, Peter Beattie, Jim Bacon, Geoff Gallop, Jon Stanhope and Clare Martin, with only Rob Kerin briefly flying the Liberal Party flag for South Australia before losing to Mike Rann. Nationally, however, Australia was an LNP stronghold. John Howard was prime minister and he was steadfast in his refusal to allow Australia to ratify the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to plan for a reduction in emissions.

Today, there is about another half a degree of global warming already in the pipeline from emissions we’ve pumped into the atmosphere over the last two decades. We’re going to have to work extremely fast to have any hope of limiting global mean warming to near 1.5°C, as agreed at the 2015 UN climate conference in Paris.

The climate lag time

The twenty-year delay in the climate system also means that even if we could magically abolish all emissions overnight, any gains we might make today would take two decades to show up in the climate signal and start bringing temperatures down again.

Is it too late, then, to do much about it? Well, yes and no. Right now, in this moment, we can’t change what the next twenty years will look like. That ship has sailed. But we can—and must—change what the following years and decades will look like by the decisions we make right now. Global warming is already bad for our health, but more warming is worse.

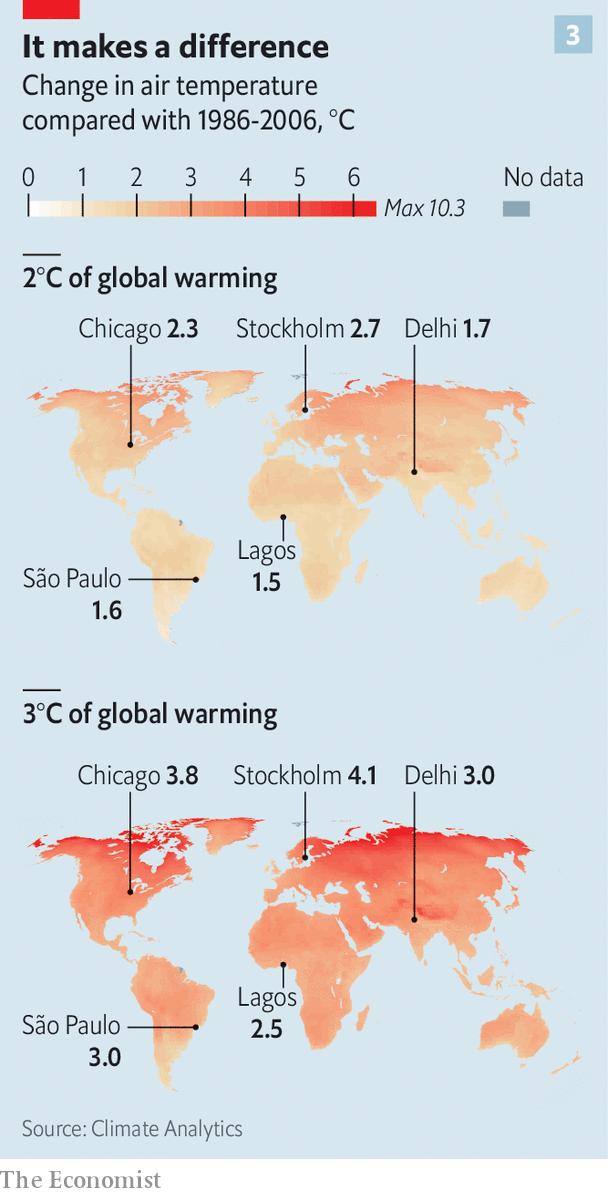

A recent report from the Climate Council exposes Australia’s delayed action and paltry emissions targets as severely inadequate and describes the steps that must be taken—now—to give us our best chance at not exceeding 1.5°C and of seeing a gradual return to a more stable climate. It explains that the federal government’s 2030 emissions targets of 26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels keep us on a course towards more than 3°C warming, which would be catastrophic to human health and to the ecosystems that support us. States and territories are showing more ambition, with their collective 2030 pledges adding up to reductions of 37 to 42 per cent below 2005 levels, in the realm of national Labor’s recent pledge of a 43 per cent reduction. It might be noted that it was pretty easy for Prime Minister Morrison to finally commit Australia, in 2021, to net zero by 2050 because this aligns with the cumulative outcome of what the states and territories are already planning. The trick seems to be to set national targets that will be met without lifting a federal finger.

But even these more ambitious targets from the states and territories and from federal Labor are not nearly enough to steer us away from catastrophe. As the report explains, to have a chance of keeping warming below 1.5°C, by 2030 Australia will need to have reduced its emissions by 75 per cent on 2005 levels. Having dilly-dallied for decades as emissions kept on rising, the cuts we need to make really are this big and this urgent.

With Prime Minister Howard, Australia lost its chance to be at the forefront of the global energy transition. The Coalition has long argued against Australia showing leadership on climate action, but now we are left well behind. Australia’s non-action on emissions is out of step with other wealthy nations, who have pledged 2030 targets that are twice as ambitious or more than Australia’s. The United States and the European Union have committed to at least 50 per cent, the United Kingdom to 63 per cent. Without more ambitious targets and the policies to match, and with billions of dollars in subsidies providing life support to fossil fuels, Australia is not taking the health risks of climate change seriously.

At only 1.1°C average global warming, Australia is already experiencing harm to health and livelihoods. It’s not just record-breaking heat we’re up against but record-breaking storms, floods, megafires and droughts. And these are merely the events that have an immediate impact on our health, through illness, injury and trauma. Other health consequences include mosquito-borne diseases, which flourish where it is warmer and wetter; food crops that are ruined by drought and storms; and pollen that is more allergenic and abundant, triggering epidemics of thunderstorm asthma. The biggest health impacts from climate change are, however, those that are even more diffuse: widespread famine; conflict and war over increasingly scarce resources; the displacement of whole populations as islands go under water or temperature extremes render some places uninhabitable.

Contrasting responses to COVID and climate

There are many parallels to be drawn between the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. They are both of our making, arising out of human actions and how we interact with our environment. They are both complex, global crises that require global cooperation that reaches across sectors if they are to be managed and solved effectively. The people who are most at risk from both climate change and COVID are those already vulnerable in some way, through poverty or underlying illness, and there are vast inequities between those countries most able to take preventative action (to meaningfully reduce emissions/vaccinate their populations) and those most at risk from inaction (lower-emitting, poorer countries). But Australia has approached the two global health emergencies very differently.

Our response to COVID-19, although far from perfect, at least recognised this emerging health crisis for what it was. The experts, for the most part, were listened to. We turned on a pin to change the way we did business and how we socialised. Collectively we acknowledged the need to transform aspects of our everyday lives, make personal sacrifices for the good of others, adopt new and unfamiliar practices and technologies, and do so quickly.

As with climate change, much of the leadership on managing COVID came from the states and territories. But the federal government, although slow on vaccines and on RATs, did do one thing spectacularly right: the JobSeeker COVID supplement. Australia nearly and magnificently—but unfortunately only temporarily—eliminated poverty overnight. For the first time many people didn’t have to choose between rent, food or medicine. We invested to protect people, and it paid off. People lived, they could afford to meet their health needs, and the economy kept ticking over.

Itching to get back to ‘normal’, government support and public health directives aimed at reducing COVID transmission were then stripped back just in time for the Omicron variant. To no one’s surprise, except, apparently, those who made these decisions, case numbers then went through the roof, testing and tracing systems failed, and health services and workers were overwhelmed. Businesses closed because staff were ill or isolating, and people took it upon themselves to stay home to stay safe. Spending in hard-hit Sydney in early January 2022 was lower than at any other time in the pandemic.

One lesson that could be learned from Australia’s handling of the pandemic—includingthe Omicron wave—and applied to the climate crisis is that the economy is people. If we fail to protect people’s lives and health, the economy suffers. You can’t have a healthy economy without healthy people to drive it. Protecting people’s health costs, but it is a worthy investment with exceptional returns.

Government is now looking to reinvigorate the nation’s economy. Transforming the energy sector to limit climate change and avoid its worst health consequences also requires investment. Where we put that money right now should be a no-brainer: a win for health and a win for the economy, with bonus rewards for the planet and the systems that sustain us.

Despite all the expert evidence, however, the decision federally is to direct COVID investment towards propping up dangerous fossil fuels through a ‘gas-led recovery’. This is neither compatible with the scientific imperative to reduce emissions by 75 per cent by 2030 nor in alignment with other countries’ targets to halve emissions in this time. Instead, it will ensure Australia’s emissions of the highly potent greenhouse gas methane will stay high for years, if not decades, to come. This is the very opposite of what needs to be done to protect health from climate change. The only solution is to go straight to renewables, fast. Much is said about the supposed costs of reducing emissions by investing in renewable energy transition, but no regard is given to the costs of inaction. And 3°C is where we are currently headed.

We’ve known about climate change and how to stop it for decades. We could have acted early. Think for a moment: if Prime Minister Howard and other global leaders had shown climate leadership in 2002, if we had pivoted to renewables like we pivoted to online meetings, we would soon be seeing a downturn in temperatures. In this fantasy scenario, climate right now would be about as hot as it was going to get, and we would soon see temperatures beginning to decline, slowly but surely. We would be looking back on the last ten years as some of the hottest in our lifetimes rather than as some of the coolest. Heat events, like the one I’m sitting in right now (the ‘feels like’ temperature has now crept up to 39.8°C and even the gaffer tape is failing) would be declining. In the years to come, fewer people would die due to extreme heat. The Black Summer of 2019–20 would be about as bad as it got.

But there’s no point regretting the inaction of the last several decades. What matters now is where we go from here.

There’s a key difference between COVID and climate change: we can’t close our borders against the latter. Climate change is a gargantuan, protracted emergency that will threaten us all if heating rises to 3°C, with obvious consequences for economy and society. Perhaps if we see climate change for the health emergency it is, government will see the threat more emphatically, and respond accordingly. Surely climate change presents us with the ultimate health crisis; isn’t it time we started treating it like one?

Fracked Futures

Kirsty Howey, Dec 2021

If production proceeds in the Beetaloo Basin, it will unleash a carbon bomb of huge proportions, and expose the Northern Territory’s environment and people to numerous other risks associated with fracking, including contamination of groundwater supplies, which make up 90 per cent of the Territory’s consumptive water use.